Karoshi “Death by Overwork” Just an Office Myth?

And as absurd as it may sound, the question must be asked: can you actually

work yourself to death, or is this just a particularly morbid twist on office folklore?

Japan’s Vocabulary for Workplace Suffering

Japan, a country that thrives on linguistic precision, has a knack for crafting

terms that perfectly encapsulate workplace agony. Take arigata-meiwaku —

the act of someone doing you an unsolicited favour that you never asked for,

which ends up inconveniencing you beyond belief, but, naturally, you must thank

them for it anyway. Then there’s majime, that terrifyingly competent colleague

who gets everything right, while making the rest of you look like slacking amateurs.

And then, of course, there’s karoshi, a word we’d rather not hear at our next

office happy hour.

Karoshi by the Numbers

By 2015, reports of karoshi had skyrocketed to 2,310, an impressively bleak statistic

that many would attribute to overzealous corporate culture, but one that most companies

still prefer to describe as “team spirit” or “dedication.”

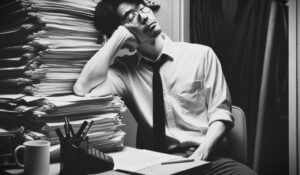

The mythos of the salary man — Japan’s workaholic corporate warriors — collapsing at

their desks has become something of a national pastime. But the true question remains:

are these deaths truly the result of overwork, or are they merely inconvenient health

issues combined with very unfortunate timing?

Could it just be that these “sudden” deaths are due to factors like bad genetics, old age,

or a tragic lack of vacation days? But let’s step back for a second and reflect on the world

we’re living in now — a time when emails never rest, Slack pings you at 2 a.m., and not

answering your phone immediately feels downright irresponsible.

Could karoshi be spreading beyond Japan, just without the catchy name?

A Typical Karoshi Case

A typical scenario unfolds like this: Kenji Hamada, a loyal employee at a Tokyo

security firm, works long hours (about 15 per day) while commuting a grueling four hours

each way. With a wife who probably hasn’t seen him awake for a while, Hamada’s life revolves around nothing but spreadsheets and PowerPoints.

One day, he’s found slumped at his desk. Colleagues assume he’s just resting. Hours later,

they realise he’s not resting. He’s dead. Age 42. Cause: heart attack.

The takeaway: corporate culture — undefeated.

The Karoshi History of Death by Overwork

This story isn’t new. The first recorded case of karoshi happened in the 1960s, when a healthy 29-year-old worker dropped dead after enduring several punishing shifts in a major newspaper office. In the words of every overworked intern: deadlines really can kill.

After WWII, Japanese workers embraced a form of work ethic that was nothing short of Olympic. Stress expert Cary Cooper points out that the Japanese once worked the longest hours in the world — not out of necessity, but with a fervor that bordered on zealotry.

Work became not just a job, but a national identity. Companies generously filled in all the gapsleft by this identity crisis, providing everything from housing and transport to recreation and childcare. Who needed a life outside the office when your employer had it all covered?

The Bubble Economy and the Breaking Point

Then came the 1980s. The “bubble economy,” as it was dubbed, turned Japan’s work culture into an even darker sport. Real estate prices soared, stock markets exploded, and sleep became an optional luxury. Nearly seven million people worked 60-hour weeks.

By 1989, nearly half of section chiefs and two-thirds of department heads were convinced they’d die from overwork. Spoiler alert: many of them weren’t wrong.

Karoshi Goes Global

The Japanese government eventually defined karoshi as death following

100 hours of overtime in one month or 80 hours across several months.

Anything less, apparently, was still considered “healthy dedication.”

The 1990s’ “lost decade” didn’t help. As Japan’s economy faltered, karoshi cases only increased, particularly among managers and professionals — and they’ve continued to rise ever since. Meanwhile, similar phenomena emerged elsewhere.

In China, it’s called guolaosi, with hundreds of thousands of deaths reported annually.

Western countries like the U.S. and the UK have yet to coin their own tragic terms for overwork deaths, but that doesn’t mean the problem isn’t there. In 2013, Bank of America Merrill Lynchintern Moritz Erhardt was found dead after working a 72-hour stretch.

What Actually Kills?

So what’s the real killer here? Stress? Lack of sleep? Surprisingly, there’s little evidence

that stress alone causes heart attacks or death. The more plausible culprit may be prolonged inactivity.

Studies show that working more than 55 hours a week increases the risk of stroke by a third compared to those who work fewer than 40 hours. So the next time you’re at your desk for the fifth consecutive hour, remember: your chair may be your silent assassin.

The Final Irony

Japan no longer works the longest hours — that title now belongs to Mexico. China continues to carry the karoshi torch forward, while the West pretends the issue doesn’t exist. Because if we don’t name it, can it really kill us?

So next time you’re at the office at 9 p.m., scrolling through Instagram and wondering where the time went, don’t stress. Staying late might not be productive, but it could be the most committed performance of all.

Karoshi: Death by Overwork

By Sayuri

https://www.bbc.co.uk/worklife/article/20190718-karoshi

https://www.bbc.co.uk/worklife/article/20160912-is-there-such-thing-as-death-from-overwork

https://www.nytimes.com/1992/07/17/IHT-japans-businesses-and-courts-find-that-overwork-can-kill.html

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43294355?read-now=1&seq=1 (the political economy of Japanese Karoshi)